Freedom By Permission

by Oleg Klimov

A short holiday from the police state—granted for football, revoked immediately after.

In 2018, Russia hosted the FIFA World Cup for the first time in its history—despite the annexation of Crimea, the hybrid war in Ukraine’s Luhansk and Donetsk regions, and the harsh persecution of political opposition inside Russia itself. By then, Vladimir Putin’s dictatorial ambitions—he is a great admirer of big sport—were known not only to the world’s political elite, but far beyond it. The public atmosphere in Russia had grown oppressive and depressive: countless new legal restrictions, detentions and arrests at rallies and pickets, the closure of independent media, and the unchecked activity of the state’s coercive machinery—police, the prosecutor’s office, the Investigative Committee, and the FSB.

And yet the World Cup happened—and, according to most experts, it was engaging and successful. The New York Times wrote at the end of the tournament: “Of course, it was not only thrilling but also very important. We may feel its consequences for years to come.”

The Independent declared with enthusiasm: “In that glorious summer of 2018, Russia showed itself at its very best, and the world smiled back.”

But let’s look at what was happening not inside the stadiums, but behind the scenes of this “best World Cup ever.”

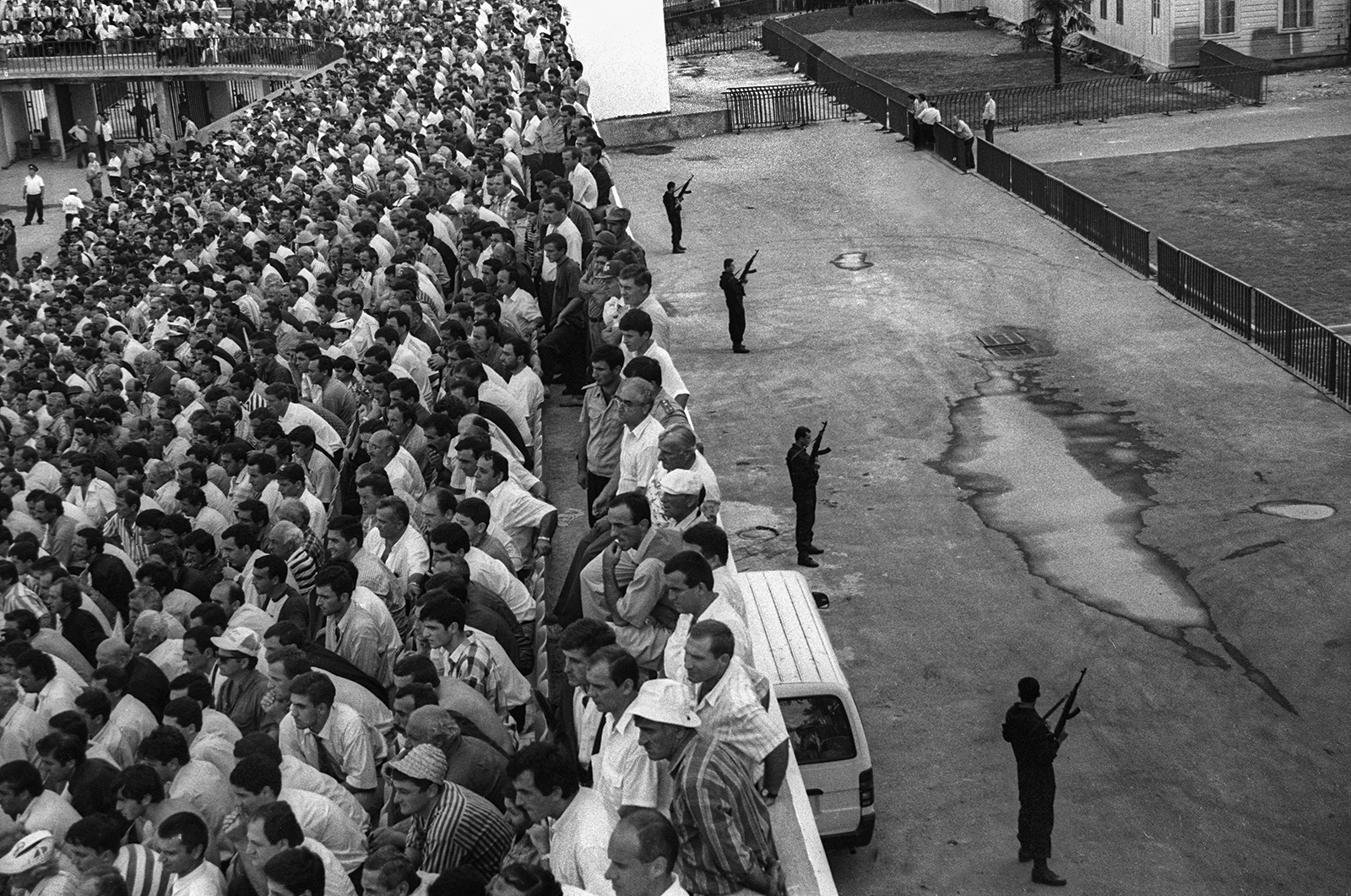

On the eve of the tournament, Vladimir Putin allowed visa-free entry into Russia for participants of international mass events—sports, cultural, scientific, and business. Entry procedures were also simplified for fans: in practice, a purchased match ticket became a pass at the border. But the main change was psychological. The familiar “police atmosphere” in Russian cities suddenly gave way to a freedom that seemed to fall from the sky. People could lie on the grass, drink beer openly in the street, shout slogans—both sporting and political—and no one detained anyone, checked documents, or threatened arrest.

This “sporting festival of freedom” did not last long—almost exactly one month, the duration of the World Cup. After that, everything returned to normal, and in the years that followed it only hardened.

For the security services—who had long governed the country using methods inherited from their predecessors, from Dzerzhinsky to Stalin—that month was a nightmare and a new kind of work. They had to monitor not only the sudden influx of foreigners, but Russian citizens too—yet not in their usual manner of “stand there and be afraid,” but discreetly and delicately, as secret services supposedly should.

The “terrorists” at the hotel

During the World Cup, our hotel’s receptionist—where I worked as the manager—received photographs of Moroccan passports. Soon after, someone from the FSB called and asked: did we have reservations for these people? The receptionist replied yes: the booking came through Booking.com. The caller then said the men were suspected terrorists and Islamic fundamentalists, and demanded that the receptionist phone a certain number the moment they arrived.

She called me. I took her place at the desk so I could meet the “terrorist guests” myself—without violating booking rules.

SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE NEW TEXTS AND PHOTO STORIES

BY OLEG KLIMOV

There were two of them: middle-aged Moroccan men. They presented the same passports the FSB had sent to us. They preferred speaking English. I escorted them to their room, and one of them noticed a Bible on the bedside table. He smirked and asked, “Is it only the Bible? Don’t you have a Qur’an?” I apologized and said there was no Qur’an—but we did have a volume of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Kant did not interest him either.

As I returned to the front desk, I felt uneasy. I began to believe that we truly had “Islamic fundamentalists” staying in our hotel. I didn’t know what to do. I sat there thinking—until one of the Moroccans came down from the third floor, approached the reception, and in Russian, almost without an accent, asked: “Do you have beer in the hotel?”

I nearly shouted: Yes! We also have vodka, cognac, and whisky. He smiled and replied, still in Russian: “Let’s start with beer. It’s better than starting with Kant. We came to support our national football team!”

They were not terrorists or Islamists. They were doctors. They had studied in Russia at the Samara Medical Institute. They had Russian wives in Morocco and lived in a suburb of Rabat.

Soon the FSB called again to confirm the arrival of the “terrorists” and demanded that we send personal data—copies of the Moroccan guests’ passports. Citing privacy law, I refused:

“Send an official written request and we will provide the data. Otherwise we have no right to violate the law. And how am I supposed to know, from a phone call, which security service you represent?”

They tried their usual method—“stand there and be afraid”—but this time it didn’t work. There was no fear. I don’t know why. Perhaps because the “World Cup freedom” had already been declared.

Another story: “my Moroccans”

Our neighbor—an elderly woman, the mother of an artist—decided to rent out her son’s studio during the World Cup invasion to earn some money. Her daughter managed to set up a Booking.com listing, but she never told her mother that foreigners might show up. And of course they did.

One day the neighbor stopped me on the street and pleaded: “Oleg, please help me. I’m renting rooms, and three foreigners arrived. They don’t speak Russian and I don’t know what to do!”

Behind her walked three young men. I spoke with them and learned they were from Morocco. They had booked the rooms via Booking.com for the World Cup, had paid, and showed their reservation on their phones. Everything was in order.

But the artist’s mother didn’t know the rules. I explained: she had to accommodate them, otherwise she would not get paid and could end up in trouble. She agreed. I helped settle the guests into their rooms.

But the story didn’t end there.

Early the next morning she called again, in panic: “Oleg, can you help me? The FSB came. They want to arrest my Moroccans—but they can’t even explain to them that they’re under arrest!”

Half-asleep, I couldn’t understand what was happening. It turned out the FSB officers wanted me to come and translate into English that the Moroccans were being detained for a document check. Five FSB officers had arrived—and none of them spoke English. The Moroccans didn’t understand what they wanted.

At first I laughed. Then I said: I can be a translator—for you personally—but I will not work for the FSB for free. Tell them that.

The neighbor didn’t call again. Later she told me that the three “my Moroccans” had been taken away somewhere. The officers told her they planned to cross the border illegally and go to Europe to live. “I didn’t believe them,” she said bitterly. “And nobody paid me my money!”

Two years after the World Cup, Russia’s Foreign Ministry reported so-called illegal migrants: “More than 2,000 foreigners who entered Russia in 2018 visa-free using World Cup fan IDs still have not left the country.” Their whereabouts remain unknown.

Of course, I don’t truly know who all those Moroccan “fans” were. But they had passports and match tickets. In a country like Russia, that is enough—only during the World Cup. Which is hypocrisy in itself.

Today foreigners do not come to the hotel at all. The borders are effectively closed. But calls from the security services and visits by armed uniformed officials have not disappeared.

Sport, the state, and “victory at any cost”

When I think about athletes rather than fans, I remember the 2014 Sochi Olympics and the later annulment of results for many Russian athletes. Investigations described a state-run doping cover-up and the manipulation of testing, involving officials and the security services.

An independent commission of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) found that systems used to conceal doping in Russian sport also operated during the 2013 World Athletics Championships in Moscow, the 2013 Universiade in Kazan, and the 2015 World Aquatics Championships.

We do not know for certain whether athletes took doping voluntarily or under pressure. But I believe coercion was possible too—under the banner of “national pride,” just as in my hotel it was justified under the banner of “fighting terrorism.”

For several years, under FSB oversight, a closed system existed at the level of the state with a single aim: to achieve victory in big international sport by any means necessary. “Winners are not judged,” they likely thought—at least that is still how it is considered in war. They did not feed athletes doping merely for personal ambition, but for the national myth of uniqueness and the so-called “Russian world,” an idea promoted ever more aggressively since former FSB lieutenant colonel Putin took power.

In Love with Football

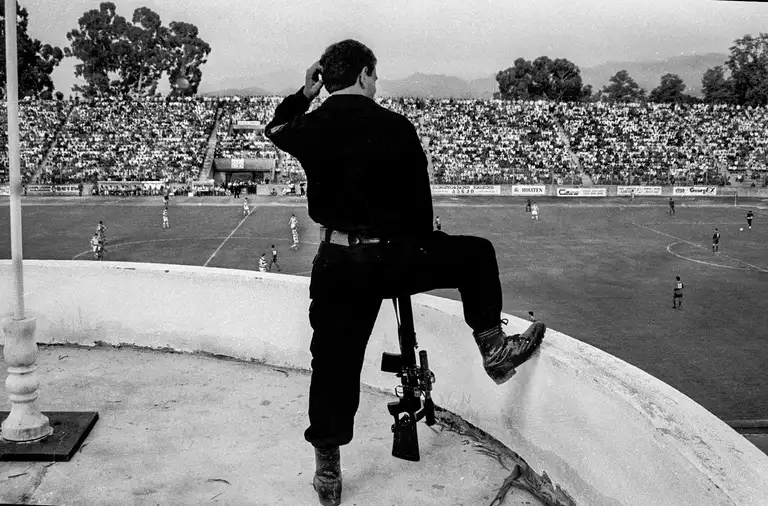

I’m not a sports fan. Yet I often see not only children’s love for football—as in these photographs—but also hear, from every media outlet, that big sport creates goodwill between peoples, and that if ordinary people could compete with each other, they would lose the desire to meet on the battlefield.

That is not true. Unfortunately, international sporting competitions often provoke orgies of hatred between people and outbreaks of nationalism between states.

I photographed this series in Moscow and titled it In Love with Football. Children play to win. The game itself is not so important; the competition is. Among these young players—and among the spectators, including me—there was no sense of local patriotism for a class, a neighborhood, or a city. Even less for a country or a state. They played street football out of love and for personal joy.

But as soon as prestige enters—school, district, city—and as soon as a spectator begins to feel that losing is “shame,” and that “winners are not judged,” the most aggressive instincts awaken. It begins with school matches and ends with international championships, where we—spectators—drive ourselves into fury over absurd contests and sincerely believe that precise kicks of a ball are a national virtue. Spectators always want one side on the peak of victory and the other humiliated and insulted.

Big sport teaches us to imitate war: sometimes with punches to the face, as in boxing, or with shooting at lifeless targets—but fortunately without deliberate killing. That is how big sport differs from big war.

SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE NEW TEXTS AND PHOTO STORIES

BY OLEG KLIMOV

When war becomes the “most effective sport”

Today there is war between Russia and Ukraine—“between Russia and the West,” Putin insists, the self-declared “organizer and inspirer of all our victories.” Can you imagine a football match today between the national teams of Russia and Ukraine? I cannot. Not because such an event would be impossible to stage with the help of international sports bodies and, naturally, with active participation of the FSB—but because “big sport” has already happened, for example, in Bucha. Not by the rules of sport, and not even by the rules of war—but it happened. After that, no sporting competition can reach such a level of mutual hatred among participants and TV viewers, because the most “effective sport” is war.

Can Russian teams compete under their national flag at upcoming Olympic Games? They cannot—not only because of symbols, but because Russia today is waging a real war rather than merely imitating it through sport, as most countries do. The issue is not only national teams that stimulate chauvinism in the “deep people.” The issue is also the spectators and fans for whom big sport becomes one of the mechanisms that generate personal aggression and nationalism.

And indeed, the recent armed mutiny in Russia showed how Russians split into those “supporting Prigozhin’s team,” fueled by his voice messages on social media, and those “supporting Putin’s team,” fueled by “urgent, fate-deciding statements” on state television. Meanwhile both groups of spectators watched, from their couches, the online advance of “Prigozhin’s team” from captured Rostov-on-Don toward Moscow and the Kremlin. Few cared about the pilots killed and civilians harmed along the way. As in big sport, only victory mattered.

But victory did not happen. That was the spectators’ main disappointment. Social media filled with images: on one side, Wagner soldiers and Prigozhin greeted in the streets of Rostov; on the other, Putin kissing unfamiliar young women—not in Moscow, but in the provincial city of Derbent in the North Caucasus. The “deep people” did not call it a sporting contest; they called it a circus—only because they saw no victory on either side. In a circus, there are no winners.

Now imagine again a football match between Ukraine and Russia.

It seems to me that big sport should belong to individuals—to specific athletes—not to backyard teams, and certainly not to teams representing states. At the Olympic Games, a person should represent themselves: their path, which they follow throughout their sporting life. What would be required for this? Simply to abolish the already fictitious representation of nations and states in big sport. To make big sport about people—not nations, together with their leaders and dictators.

Maybe then big sport would imitate not war, but peace.

Oleg Klimov, freelance photographer