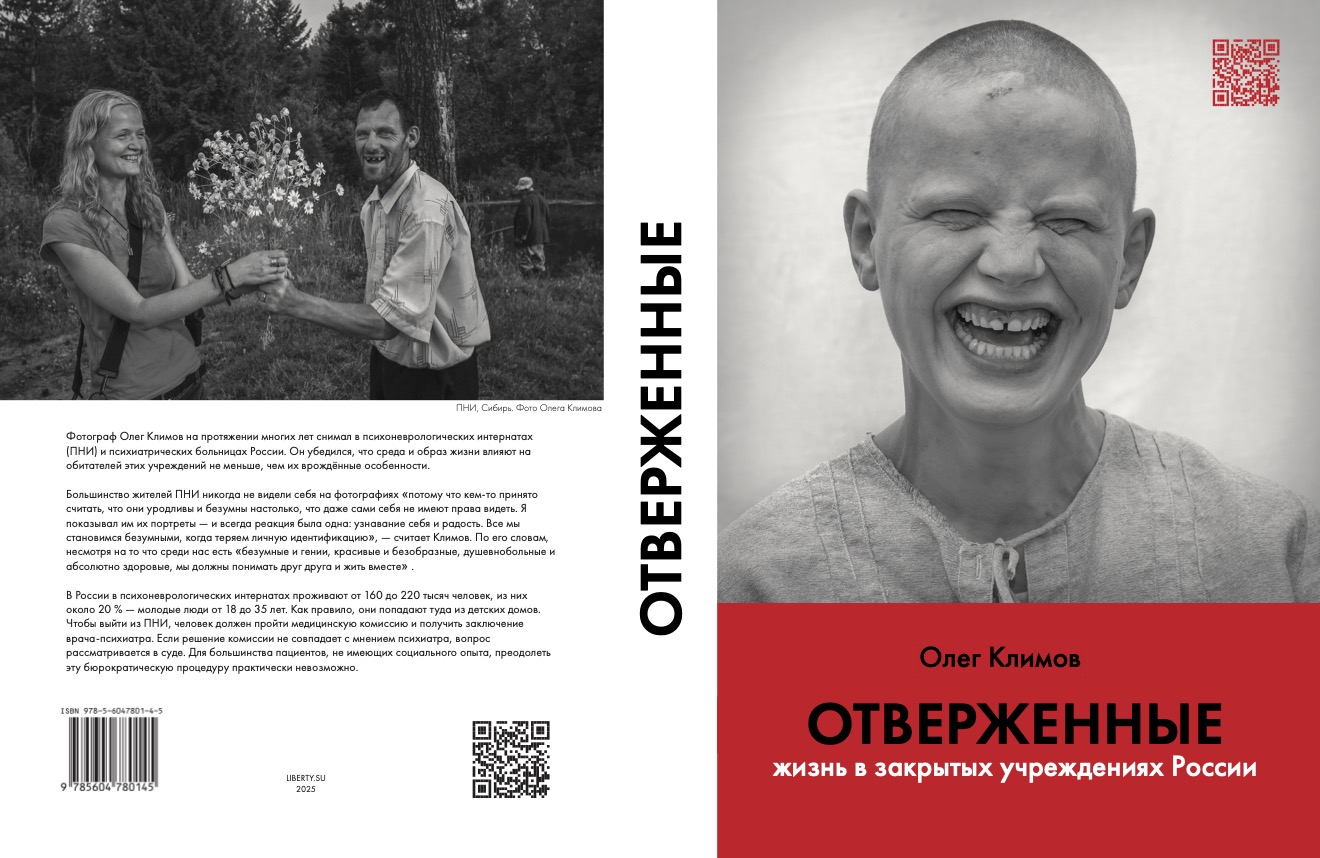

THE OUTCASTS

by Oleg Klimov

Life Inside Russia’s Closed Institutions

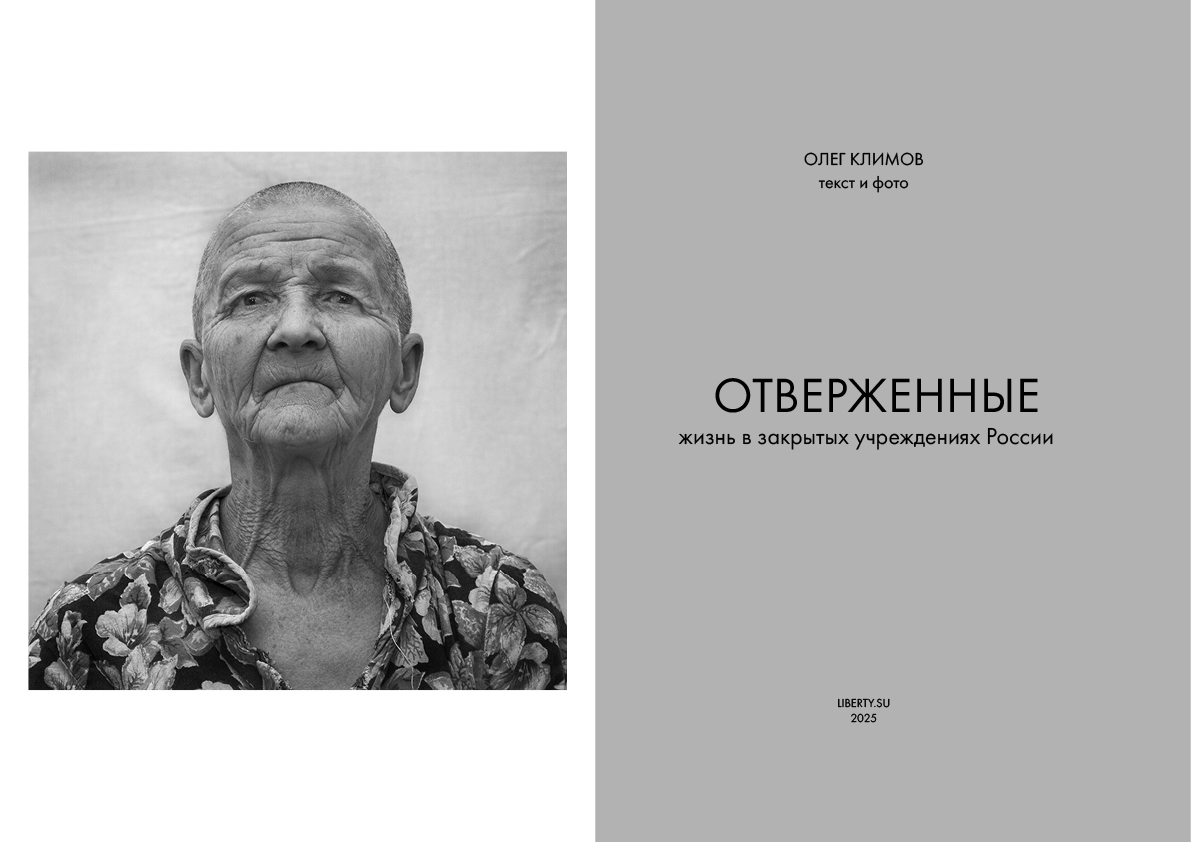

I spent a total of three months in a residential psychoneurological institution (known in Russia as a PNI). During that time, I made approximately 500 portraits of its residents and observed daily life inside one of Russia’s most closed and stigmatized institutional systems.

Over time, I stopped using knives and forks—only spoons were permitted—saw a Russian Orthodox iconostasis installed in the cafeteria, and shopped at a store where no one ever uses cash, as residents are never given their pensions directly.

While getting to know my neighbors and teaching them mathematics and photography, I became convinced that a person’s environment and way of life shape them at least as much as the traits they are born with.

SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE NEW TEXTS AND PHOTO STORIES

BY OLEG KLIMOV

In the spring of 2025, I held a small exhibition presenting the future book in Saint Petersburg. The exhibition ran for two weeks at the Lermontov Library on Ligovsky prospect, until one visitor filed a formal complaint, accusing me of implying that my exhibition about people with mental illness portrayed Russia itself as a psychiatric hospital.

Paradoxically, the woman who wrote the complaint was, in a certain sense, partly right—although I have never stated this openly. In my defense, I can say that Russia today is not only psychologically unwell, but has also, in many ways, become an outcast itself.

From the outset, I planned to publish THE OUTCASTS as a bilingual book, in both English and Russian. For now, however, I have only been able to raise funds for printing in Russia, thanks to crowdfunding on the Planeta.ru platform. This is my first book published in Russian, and I am genuinely happy about that.

Will it be published in English or Dutch? I am far from certain, given the prevailing perception of Russia as a country of “outcasts.” I say this as someone who has worked for international mass media for more than thirty years and who today experiences not only the global crisis of photojournalism, but also a very specific attitude toward the “Russian passport” I carry—alongside my press credentials as a photojournalist.

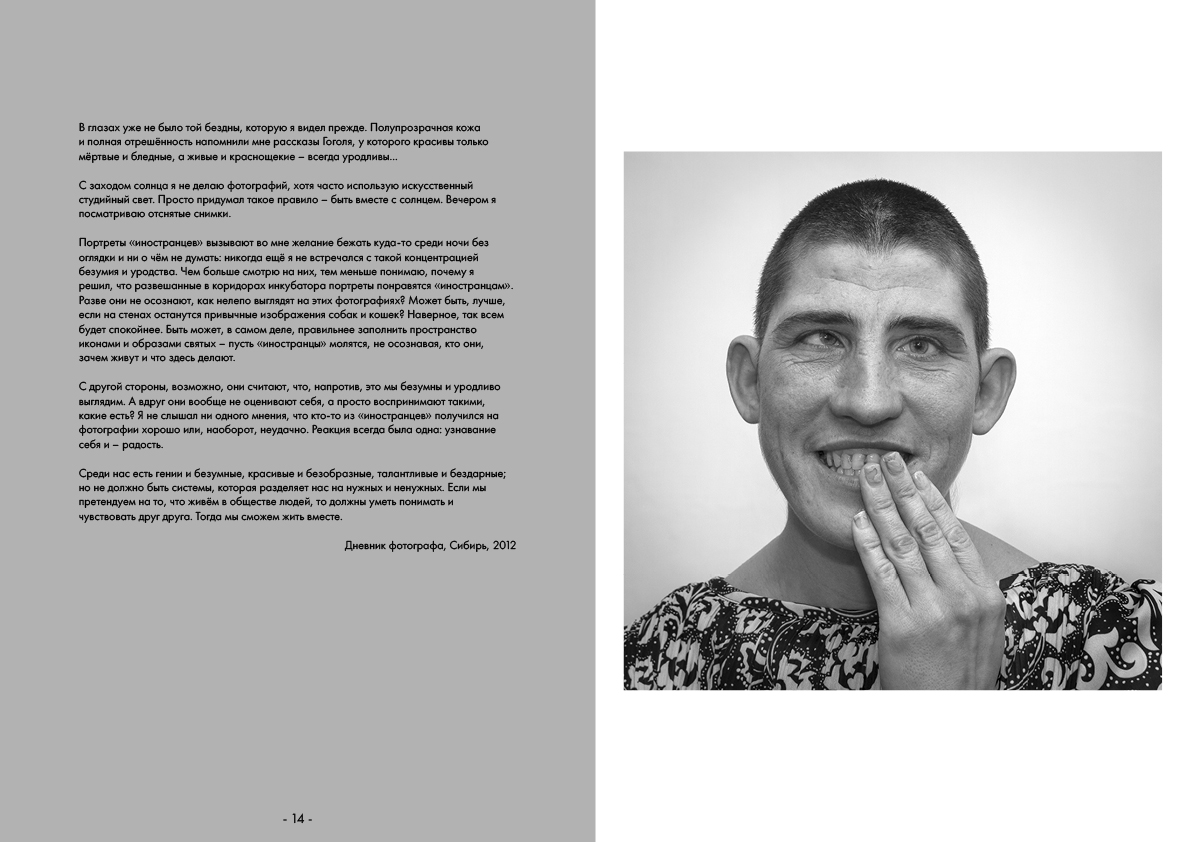

At some point, someone decided that it was acceptable to treat them as so ugly and insane that they did not even have the right to see themselves. When I showed them their portraits, the reaction was always the same: recognition and joy. We lose our sanity when we lose our personal identity.

Even though there are geniuses and people considered insane, people judged as beautiful and ugly, people diagnosed with mental illness and those who consider themselves completely healthy, we must learn to understand one another and live together.

Oleg Klimov, Photographer’s Diar

Share information — help keep the world free: