The Story of One Photograph

by Oleg Klimov

The true heroes of this story are not generals, and not even soldiers. The real heroes are the mothers.

We photojournalists are always searching for visual meanings that might convey the essence of what is happening. Published in the mass media, people depicted in photographs tend to lose their individuality; they turn into abstract figures. At best, an editor will add a caption stating what happened, where, and when. The history of photography is full of such abstractions.

In January 1995, an attempted prisoner exchange took place in the detention facility of the Shali Department of State Security of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. In return for the release of Russian soldiers, the Chechen side demanded that “rebels” detained by federal forces be freed. After negotiations, the Russian side refused the exchange. The Chechen authorities then decided to execute the Russian prisoners—but before doing so, they allowed soldiers’ mothers to visit them. These women were searching for sons listed as missing in action.

This was January 1995, the very beginning of the First Chechen War. I was there as well, accompanying the mothers to the Shali detention center. About twenty prisoners were being held there—fighters from the 22nd GRU Special Forces Brigade of the Russian Ministry of Defense.

The woman in the photograph recognized her son and rushed toward him. I was standing nearby, hearing her cry, whisper words to him, embrace him. Despite the tears and the horror of the situation, she looked unbelievably happy, her hands resting on his shoulders. Journalists were given only a few minutes to photograph. Then we were escorted out of the prison. I would find that soldier again only twenty years later.

At the time, it never occurred to me that I would have to search for him. I didn’t even ask his name; there was no reason to. But years passed, and I began to look for him.

I published that photograph dozens of times and showed it at exhibitions in different cities and countries. Eventually, I handed it over to the international organization Mothers Against War, which printed large posters and displayed them across Amsterdam. But the war continued. I began to understand that photographs, by themselves, do not stop wars. And then it occurred to me that the fate of that soldier might be far more important than the “visual symbol” I had created twenty years earlier.

I searched for him with the help of many people for nearly a year. The task was complicated by the fact that the prisoners in Shali were GRU soldiers—an organization that provides no records. It was also not a standard, well-planned operation. The special forces unit had been dropped into the mountains on New Year’s Eve without clear objectives and, as later became clear, using military maps from 1941.

The main fighting was taking place around Grozny. In the mountains, there was silence—only shepherds lived there, and the special forces had no intention of fighting them. For several days they wandered through forests and mountains searching for a “probable enemy,” until they eventually detained two shepherds—one of whom possessed a hunting rifle.

A few days after the drop, the unit was surrounded. The shepherds informed the Chechen security service that hungry, freezing Russian soldiers were roaming the mountains for no apparent reason. A firefight followed. One soldier was killed, another wounded. The Chechens proposed negotiations. Major N. went to negotiate and returned with a proposal to surrender.

“When the war had just begun,” the major explained to me when we met in 2013, “there weren’t yet many casualties. Not everyone had lost friends or relatives. There wasn’t that kind of hatred yet—the kind that makes people kill each other inside their own country. We were dropped into the mountains of our own land. We met no resistance and didn’t understand whom or why we were supposed to attack. We didn’t know that thousands of soldiers had already died in Grozny. For us, there was still peace.”

“It was incredibly hard and humiliating to surrender,” almost every soldier I later found told me. “Special forces don’t surrender. Russians don’t surrender.” And then, as if apologizing: “But thanks to the major, we survived.”

The Chechen fighters initially wanted to execute everyone publicly in the town square. But Major N., a veteran of the Afghan war, encountered a former Afghan comrade among the Chechen field commanders. That coincidence kept negotiations alive. The major was offered the chance to defect to Ichkeria. He refused. He was then offered a chance to escape. He refused again, unwilling to abandon his soldiers. The brotherhood forged in one war made it difficult to become enemies in another.

When the Russian command learned that the unit had surrendered, it officially declared all of them dead. The location where they were held—known to the command—was soon subjected to air strikes by federal forces. To keep the prisoners alive, the Chechens were forced to constantly move them. Even the Chechens were shocked by the attempt to destroy their own soldiers. The prisoners themselves could hardly believe what was happening. “Everyone wanted us dead,” one of them told me twenty years later.

It was at that moment that the idea emerged to invite soldiers’ mothers and make the story public—partly for propaganda purposes. That was the moment when “my soldier” was embraced by his mother.

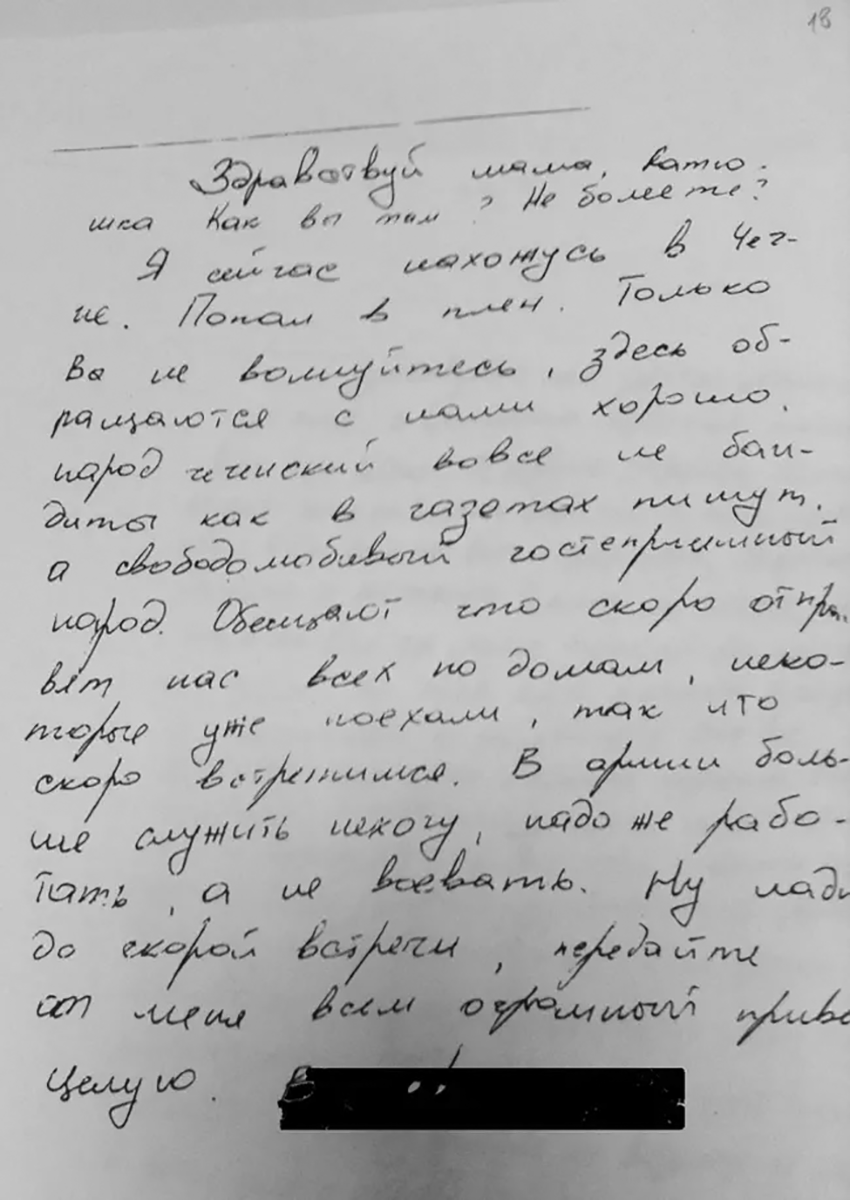

Years later, I began my search at the Moscow Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers. One of its staff members remembered that the soldiers from Shali had written letters home—and that those letters might still be preserved in archives.

We searched through the archives of various municipal and federal institutions. While reviewing lists of the dead, execution records, and documents detailing betrayals, I came across one letter from Shali. From there, the search became easier. We found more than a dozen letters written by prisoners to their mothers. The handwriting was hesitant, childlike, filled with spelling mistakes—possibly dictated. The same phrases appeared again and again: “Mom, I’m fine. I’m in Chechen captivity. They feed us well… Mom, please come and take me away from here.”

It was the most terrifying wartime reading I have ever encountered. The envelopes bore return addresses. That made it possible to continue the search.

SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE NEW TEXTS AND PHOTO STORIES

BY OLEG KLIMOV

None of the women—the mothers of the GRU soldiers I eventually found and spoke with—wanted to relive those days. At the word Shali, they would begin to cry quietly. And yet, incredibly, they managed to save their children. Thanks to the mothers and public pressure, the Ministry of Defense was forced to agree to a prisoner exchange. It took place in April 1995.

An unarmed GRU unit was escorted under guard to helicopters that were supposed to take them to a military base in Mozdok. The mothers were forbidden to fly with them and were ordered to remain in Chechnya and return the same way they had arrived.

“We stood there, not knowing what to do,” one mother recalled. “The son I had searched for so long, who turned out to be alive—was being taken away again. I couldn’t take it and ran toward the helicopter. The mud was impassable. I kept falling, getting up, running again. When the others saw me, they ran too. The helicopters were already lifting off, and the soldiers began grabbing us by the arms, pulling us inside. We could no longer abandon our children.”

I continued my search and eventually found Major N. We met early in the morning at a small bar in Moscow. He arrived straight from a night shift. Now he works as a security guard for a private company outside Moscow. A retired major.

“I want to pass on greetings and thanks from your soldiers and their families,” I told him. “I’ve met some of them. They asked me to do this. They also want to see you.” It sounded banal, even awkward. He stood there in his guard’s uniform, clearly uncomfortable. But I could see gratitude and pride in his eyes. No one had ever said such words to him before.

Soon afterward, I traveled to Rostov to meet “my” private. His name is Roman. He met us at the train station and drove us home in an old Lada. After captivity, he was immediately discharged from the army, as were the others. He was threatened with prosecution under an article criminalizing surrender, which at the time could mean up to ten years in prison—or even the death penalty. In the end, nothing came of it.

For a time, Roman was unemployed. A career military background helped him find work in a police special unit. Later he was transferred to a rapid response unit, and the war continued for him. He returned to Chechnya during the second campaign, suffered multiple concussions, and received combat medals. During a short leave, he married. He now has two children. The family had to buy an apartment jointly—he never received anything from the state “except medals that rattle like toys.”

“I’m forty now,” Roman told me. “I’ve spent the entire second half of my life on assignment—at war. Do I regret it? I don’t know. But I want my children to live in a different state, or in another country. Strange, isn’t it—to give your life to a state and wish your children would never live in it? But that’s how I feel.”

“Am I grateful to my commander? He probably doesn’t remember me. But without him, there wouldn’t be me—or my children,” Roman continued. “I’m a commander myself now, and I don’t know if I could make the same decision, take that responsibility. We could all have been executed. Commanders are given the right to send people to their deaths—but not the right to preserve life at any cost. He knew his career was over. And still, he chose that path.”

I wanted to meet Roman’s mother as well, but she refused, citing illness. Roman later admitted that she simply did not want to remember those events. Or speak about them.

On my way back, I thought about how, for twenty years, this story had existed only as a brief caption beneath a photograph: “A mother finds her son in Chechen captivity. Shali, Chechnya, January 1995.” Now it meant something entirely different to me. It was no longer the personal story of one soldier. It had become a story about the horrors of that war.

And I believe the true heroes of this story are not generals, and not even soldiers. The real heroes are the mothers. I remember them wandering through the ruins of Grozny, holding photographs of their children, asking locals and soldiers whether anyone had seen their sons. They were not allowed into military units and were often told that the Ministry of Defense “does not deal with the dead or missing.” They lived among the ruins, warming themselves by fires. Some found their children. Some died themselves.

Their personal struggle stood in direct opposition to the interests of the state—and saved many lives. In a war where, as one Russian general once told me in Chechnya, “a human life is worth nothing when the life of the state is at stake.”

Oleg Klimov, Photographer’s Diar

Share information — help keep the world free: